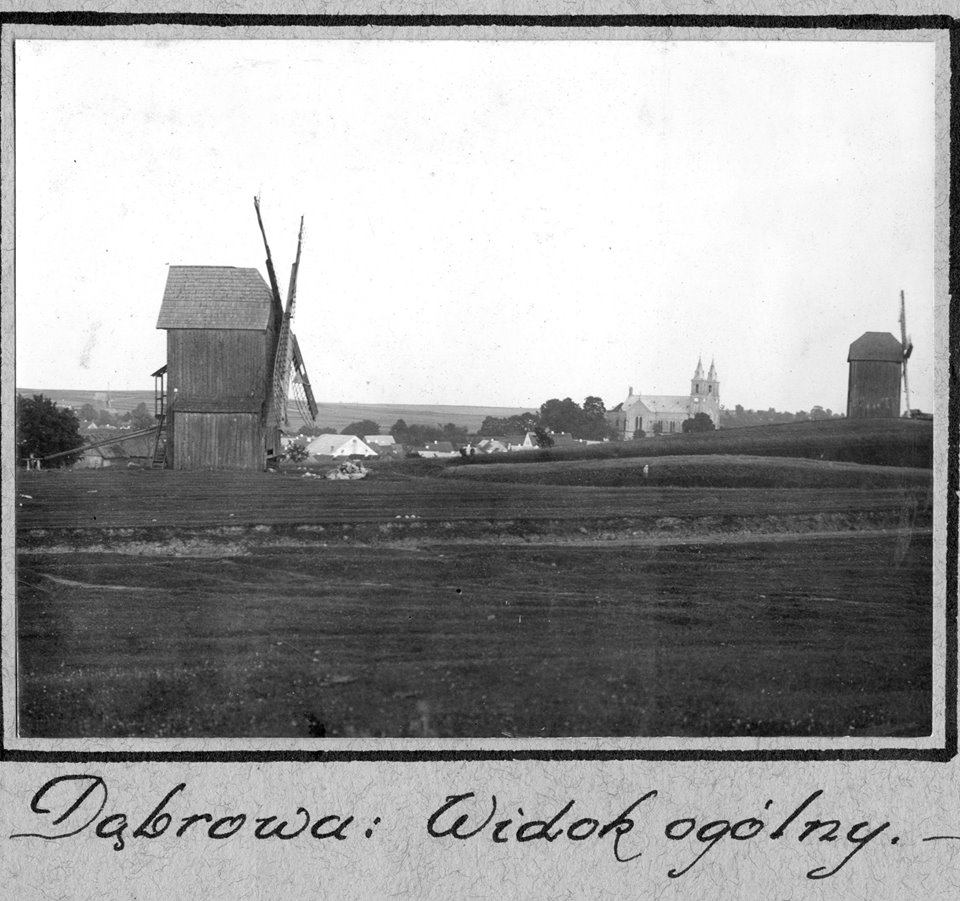

Dąbrowa Białostocka - the outline of history

Dąbrowa Białostocka - the outline of history

The beginnings of the

town are dated back to the second half of the 16th century. Piotr Wiesiołowski, Court Marshal of

Lithuania founded the church in the

village Małyszówka and equipped with a mill and surrounded by six land levelers

of ground . It was confirmed on 12 April 1595 by the privilege dated 29 January

1595. The church was built in Małyszówka in the place called Dąbrowa. Dąbrowa

was the part of the village Małyszówka constituting ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

The name Dąbrowa is a topographical name which means the oak forest. This type

of forests was an object of pagans worship, mainly the Balts – Sudovians and the

Lithuanians. Not without reason Christianity

located its religious centers in these primeval holly places. The similar

situation occured in Korycin which initially was called Dąbrówka. In written source materials

terminology Dąbrowa with reference to the place where the church worked, appeared initially in 1616 and 1617.

The information about

fairs, taking place on Sundays and

religious holidays near the

church, and the guest house appeared in 1650. In the first half of the 18th

century the settlement was mentioned in

the documents as a village. Only once in 1712 in the

inventory of Nowy Dwór forestry it was mentioned that the beekeepers lived in

Dąbrowa town. The most important document, which certified that Dąbrowa was a

town, is king August II royal privilege dated 8 March 1713 giving the town

fairs and rights for Jewish people.

This document is the

first certificate – royal privilege confirming city charter to Dąbrowa. It was

said that Dąbrowa was given the city charter between 1768 – 1775 as a result of

Antoni Tyzenhauz – Lithuanian treasurer efforts. During that time Tyzenhauz

changed the visage of Dąbrowa by measuring the market and building several made

of bricks houses. In fact, none of the privileges based on Magdeburg’s law, was

established and Dąbrowa was a typical urban center in our region, so called a

small town. Apart from the trade exchanging and craft concentration, the urban character

of the town was proved by numerous Jewish people living there and dealing with urban

activities.

Jews appeared in Dąbrowa

in the first half of the 17th

century. Their settlement can be associated with functioning of nearby church

fairs. In 1650 it was reported “ the

guest house near [ …] gardeners [ Kamienna manor ] and the second in the

village Dąbrowa near the church where market used to take place on Sundays and

holidays”. The beginnings of Jews settlement ( arguably several of them )

in Dąbrowa should be connected with Poświętne parish priest who had six drag

benefice in Dąbrowa.

In the half of the 17th

century individual Jews also lived on the royal grounds. They were dealing with Kamienna manor’s grounds , taverns and

mills leasing. It was evidenced in the inventory of Grodno

royal treasury dated 1650 in which Jew-

tavern renter – was mentioned. Another Jew rented three mills in

Kamienna.

There is little information about Jews in Dąbrowa at the

second half of the 17th

century. Perhaps their number increased enough for founding separate Jewish religious

community which was probably like other

surrounding communities, przykahałem- a part of Grodno province. When the king passed the fairs

privilege for Dąbrowa in 1713 it was said in it that Jewish school called bóżnica, baths and cemetery had already

existed in Dąbrowa. They were all necessary elements for having their own religious community. It

was also stated that there were no fees for them. The inspector describing

manor incomes in 1712 stated that: “Nowy

Dwór forestry leasing under one contract, which owned an alcohol tawern in Kamień

dominion, which should be one only, but with the settlement of Jews on

Poświętne place in Dąbrowa and settling them on the royal rural grounds, they

all sell alcohol in rented taverns and several Jews settled in the villages”. This

notation proves that more significant

Jewish settlement in Dąbrowa was then a relatively new issue, especially on the

royal grounds in Dąbrowa and in relation to Jews leasing taverns in surrounding

villages. Jews as townspeople inhabited mainly Dąbrowa and their history is

connected mostly with this town where community owned a synagogue, houses of prayer, schools and graveyards

existed.

In 1789 it was mentioned

that there were 39 Jewish houses where 135 people lived and 10 Christian houses

( 49 people ) in Dąbrowa town. Furthermore,

an inspection in Dąbrowa parson’s property

showed 32 urban houses where 137 lived, 10 retinue and no Jews.

Moreover, there was the royal village

Dąbrowa – 17 houses with 67 people and Dąbrowa government with 3 people. In

spite of having different owners and the distinction between a village and town

Dąbrowa, it was one unity. And the mentioned Jews were 1/3 of inhabitants of so

understood Dąbrowa. In the next inventory in 1792 it was noted down 58 Jews, 9

Christians and Tatars.

Prussians treated the

town and village Dąbrowa, Dabrowa’s government and parson’s property like one

unity – the town Dąbrowa. At the turn of 1799 and 1800 the location was

inhabited by 737 people – 283 Jews that was 38% of the inhabitants. In 1807 at

the end of Prussian governance, there were 481 Jews that constituted 54% of the

inhabitants.

In 1880 Dąbrowa was

described as nadetatowe town of Sokółka district with 207 houses and

1438 inhabitants ( 685 men and 753 women ). Among inhabitants, there were 1132

Israelites, 264 Catholics, 29 Muslims and 13 Orthodox. And there were 9431

people I Catholic parish.

An important event in

the town existence was the raising of

the new big and made of brick church. The notable priest Józef Fordon undertook

this construction between 1897 – 1902.

In 1904 in Dabrowa there

were 1800 inhabitants and the Jews were 78,2% of all inhabitants. It was the

highest rate of Jews in whole Grodno government and one of the highest, if not

the highest, in Russian empire. The

Polish ( 19,2%), the Russian ( 0,7%),and Tatars ( 1,7% ) living there

were in minority. The markets and the streets were not cobbled. There were not

pavements or street lights. There were 250 houses but only 3 were layed with

stone. The houses were wooden with made of straw ( 120 ) or wooden ( 120 )

roofs. Only a few of them were roof tiled ( 10 ). The houses were built in

quite little space hence great population density and crowd. The town area,

similar to Korycin area, was the smallest in Grodno district ( Gubernia grodzieńska ). There were no waterworks, a sewage

system, a doctor, a library,a fire station, a photographer or a hostel in the

town. There were 5 shops, 11 taverns, a small factory employed 3 workers, 2

primary schools, 3 Jewish houses of prayer, the pharmacy and a military

surgeon. An interesting historical source concerning Dąbrowa and its

inhabitants – Jews is the so-called memory book: “Dubrowa. Memorial to a Shtetl”. There were mentioned, for instance

the buildings connected with worship in

this book. It was mentioned Beis Midrasz ( Beis ha Midrasz or Beit ha Midrasz )

which means Jewish “Study House”, it

was also intended for prayer. It existed already in 19th century. In

the book it was also mentioned “Szul”.

It means synagogue in Jidisz. But it emphasizes its character as a place of

studying, school. Supposedly it became in 1874 thanks to rabbi Menachem Mendel.

It was a big made of brick building. It was used only on Saturdays and more

significant holidays. The building was not heated , therefore “ people had to be close to each other”. The

emigrants from 1920s mentioned that “older

generations were more engaged in obeying

the Jewish laws”. The location of the Synagogue ( Szul ), the Study House (

Beis Midrasz ), the baths ( mykwa ) and two Jewish graveyards ( old and new )

is shown in Abraham Gusewicz’s ( Gushewich ) mind map showing the situation from

the interwar period.

Daily life of Jews in

Dąbrowa oscillated between a house, usually detached house, the synagogue and

the market. The houses were usually two-room. In the bigger one there was a

shop. It was also used as the dining room

during a day and as the bedroom at night. Behind this room separated by a stove

there was a smaller one which was used as the kitchen and the bedroom. Most

families also owned a cowshed, a stable and a henhouse. They often rented

grounds from Polish people. They mainly grew potatoes. In the visitor’s book of

Jews from Dąbrowa it is mentioned several times that the main source of

livelihood was trade. The smuggling is mentioned once. “The Russian government was corrupt so life was based on fraud “– it is mentioned in the book. There

is no information about the craft, which according to the statistics, was the

main source of livelihood of over half of the Jews living in a town.

In 1921 in Dabrowa there

were 566 houses and 3014 inhabitants. Among them there were 1218 Jews, 1717

Catholics, 46 Orthodox and 33 Muslims. 1751 people had Polish nationality, 1206

- Jewish, 33 - Tatars, 22 – Belorussian and 2 – Russian.

Before the World War II

in Dąbrowa there were 2 engine mills

and 6 windmills, tile factories, a place where wool was carded called “gręplarnia”

– carding mill, a dye shop, an oil factory,

a dairy cooperative, People’s Jewish Bank. There were also the post office, the

police station, the pharmacy, 2 doctors, the council, municipality, school. Many

different associations and organizations

worked in a town : Agricultural Group, Catholic Youth Association, Reservist

Union, Women’s Civil Work Union, Shooting Union, Sea and Colonial League, Air

and Gas Defense League, Association Supporting Public Schools Building.

During World War II the

town was almost completely destroyed and the Jews were murdered ( holocaust ). In

1950 there was deprived Dąbrowa of city charter. In 1956 Dąbrowa became the

district headquarters and it had impact on its development and regaining city

charter. After an administrative reform in 1975 Dąbrowa district was abolished.

1960s and 1970s of the 20th century it was a quick development of

the town. Many manufacturing plants developed where townspeople and the

inhabitants from surrounding places were employed.

dr Grzegorz Ryżewski ( National Heritage Institute )

tłumaczyła na język angielski Elżbieta Kondracka